Why Ministers Lose Moral Credibility in Business and Public Life

This article presents a rare insider assessment of the clerical profession written with unusual candor. The author examines why ministers, while not more criminal than other professionals, suffer lower moral and commercial esteem in business and public life. Drawing from real cases, the article highlights unpaid debts, broken promises, and weak commercial ethics linked to clergy behavior. It explores structural causes such as inadequate compensation, dependence on congregational favor, lack of professional ethics training, intellectual dishonesty, and the moral strain of preaching ideals not consistently practiced. The piece argues that hypocrisy, flattery, fear of heresy trials, and poor institutional support erode character and credibility. It concludes that honest preaching, fair pay, ethical training, and practical engagement with everyday work restore respect for ministers and the church.

This excerpt is from the book “Crimes of Preachers in the United States and Canada” is an early‑20th‑century freethought polemic that attacks the claim that Christian ministers are more moral than ordinary people in the society, using newspapers’ own reports of clerical wrongdoings as evidence.

The book opens by explaining that it is a reply to preachers who say unbelievers are immoral and that Christianity is necessary for good conduct; the author argues that if this were true, ministers themselves should display especially high standards, yet the record shows otherwise. A substantial introductory essay sets out the logic: systems should be judged by the correspondence between their moral claims and their fruits, and since clergy enjoy social privileges (tax exemptions, Sunday control, public deference), it is legitimate to scrutinize their behavior in the workplaces and marketplaces.

The central section compiles hundreds of brief case summaries of ministers in the United States and Canada accused or convicted of crimes and serious misconduct, organized by name, denomination, offense, place and year. Offenses range from abnormal sexual immorality (seduction, bigamy, rape - “immoralities with underaged girls”) and domestic cruelty to financial crimes (embezzlement, fraud, forgery), violence (assault, manslaughter, murder), drunkenness and other breaches of law and ethics. The book includes a statistical table counting instances of each offense type, showing particularly high numbers for adultery, desertion, larceny, and “immoralities with women and girls,” and notes that while Methodists and Baptists supply many names, this largely reflects how numerous and loosely screened their clergy are, the Pentecostals play the self righteous-holier than thou disposition that they cover up their actions.

The book also criticizes institutional protections enjoyed by clergy, especially Catholic priests, such as requirements that ecclesiastical superiors approve prosecutions, which, the author says, conceal many offenses from public view. Several illustrative anecdotes show ministers receiving unusually light sentences for serious crimes (including sexual offenses against minors), contrasted with harsher efforts to prosecute lay offenders, which the author presents as “benefit of clergy” surviving in modern form.

Throughout, the author insists that the catalogue of crimes does not “disprove” Christian doctrines directly, but undermines the specific clerical claim that belief in Christianity guarantees or uniquely produces moral behavior in societies. The closing sections reiterate that many ministers are personally upright, yet the profession as a whole cannot credibly claim moral superiority over nonbelievers when so many of its own members have committed serious offenses, often while preaching rigorous piety. The work ends with publishing information, references to earlier editions, and promotional material for other freethought books and for The Truth Seeker, the freethought journal that issued the volume.

The article, whose author is a minister, is surprising mainly because of its frankness and not because it tells anything not previously known or surmised. The writer says:

“Do ministers of the churches, that is clergymen, priests and preachers, go wrong in any greater proportion than do doctors, lawyers or teachers? If one answers the question mathematically, no; if one answers the question in the light of our moral standards for ministers of the gospel, the negative answer will not be so readily and decidedly given. There are few issues of the daily newspaper without at least a single item narrating the fall of a clergyman. It would be hard to find a man or a woman who has not at some time in life become personally acquainted with a professed exponent of religious truth and high moral ideals who has demonstrated the depths of human depravity.

“Yet the indictment against the profession is of a much more subtle character than that found in journalistic annals of crime or even in personal knowledge of gross faults on the part of clergymen. It would be folly to deny that, taken as a class, ministers live lives as pure and as free from criminal or grossly immoral taint as any other class of persons. The indictment takes rather the form of a general impression, amounting almost to a conviction, that the minister does not have the clear-cut and high standards which the business world demands.

“Business men feel that there is something about the ‘cloth’ that makes its wearer a ‘doubtful proposition’ when it comes to square dealing between men. A prominent lawyer in Chicago said, only the other day, ‘I dread seeing a clergyman enter my office; I do not want his business; he does not have the commercial honor of the man of affairs.’ He went on to give instances of ministers who disregarded their business obligations and even ignored the sanctity of the oath at the bar of justice.

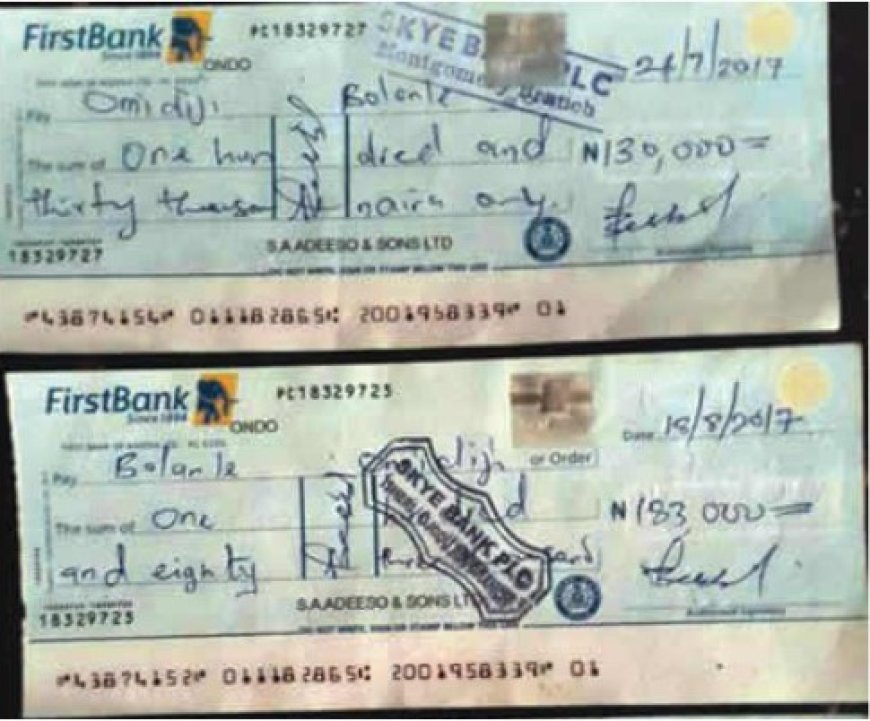

“It is a well-known fact among houses accustomed to extend credit that ministers are the slowest to pay, and the most difficult from whom to collect. In the smaller towns it would be difficult to find a grocer without an uncollected account against some minister who had left the place. Over five years ago such a preacher boasted in his farewell sermon that all his bills were paid in the village, and he ‘owed not any man’; he should have said that he had paid not any man, and some of his bills are still unpaid.

“A charitable organization in Chicago allowed a minister in a village nearby to become indebted to it. He promised to pay the small account at a certain date; but a year from that time, although many letters had been written, the bill was unpaid. Nor was settlement made until this prominent minister on a good salary was sent a sight draft for the amount.

“A struggling professor in an Eastern city consented to pick out a few books for a preacher up State, and to have them charged to his own account, being assured that payment would be made at once. The books were sent, but the cash never was forthcoming, and after a lengthy correspondence, in which many excuses were offered, the professor had to count his loss as the price he had paid for a lesson in trusting the ‘cloth.’

“Such evidence could be extended indefinitely. The facts back of it, with the many other instances of which these few are but slightly indicative, have produced the decided opinion in the business world that the minister is unreliable, and that the ministry does not stand of necessity for admirable manliness.

“There are many exceptions. The manly, four-square ministers are the more noticeable because they are exceptional. There are still more ministers who are warmly admired by their congregations, but they are admired rather for professional traits and pulpit graces than for the rugged virtues that count on the street and in the store and office. On the whole, men of honor feel that today it is no honor to be entitled ‘Reverend’; the average man looks somewhat askance at the clergyman.

“Perhaps this is nowhere better illustrated than when a minister leaves his profession and desires to enter business. He finds there a strong prejudice against his past; it is regarded as unfitting him for work. When such a man goes into an office, experience shows that he is likely to lack the qualities that make for trustworthiness in details in the individual and for harmony in a large force of employees.

“Now, if the business of the minister is to teach the people how to live, he ought at least to know how to do it himself. His principles are valueless if they will not stand the wear of daily life. Is the trouble with the teachings, with the message, or is it with the man himself?

“The first reason ministers go wrong is because they are men. They are not angels; they are not the reincarnated ideal saints that the sisters and the sisterly brethren like to think they are. Because they are men they have human frailties. But, while that does account for the fact that ministers steal and break the express commandments the same as other men, it does not account for the fact that they are held below par in commercial transactions otherwise let them stay only in their pulpits and not engage in any financial related transactions.

“As a profession the ministry seems to offer a premium on the pretender, the impostor, the hypocrite. So long as there are the intentional pretenders and the unconscious hypocrites in the church they will enjoy the ministry of the pretender and hypocrite. So long as the churches say, ‘There’s nothing either good or ill but seeming makes it so,’ the man who can succeed in fooling the people with appearances of virtues, with saintly air and pious phrase will be the man who reaches the top of his profession.

“Then no mortal being can stand for long the fawning and adulation which the preacher is likely to receive, especially from foolish and emotional women. He is sure to come to believe that he is a superior being, one who either can do no wrong or can do only right. Steady feeding on flattery unfits him for sound counsel regarding his shortcomings; he gets into the habit of judging his own actions, not by any undeviating principles, but by the measure of praise they receive.

“Mere preaching puts a tremendous strain on a man’s moral fibre. It is the habitual statement of duties and ideals which the preacher knows he does not reach and do. It is the expression of the phrases of character, not necessarily accompanied with their expression in living and doing. It results in the mental habit of considering a duty done as soon as it is declared. It exhausts the moral impetus in phrases. It makes the man act the lie.

“Intellectual dishonesty results from habitual standing as a special pleader; as the defender of ground which has not been honestly, candidly examined. The preacher seldom goes back to the evidence; he argues from the conclusions of others. He stands as an authority in that in which he frequently has made no original, unprejudicial examination.

“Intellectual dishonesty comes as a result of cowardice in regard to the declaration of his own honest convictions. He is perhaps unconsciously persuaded to teach what the church teaches rather than what he would teach if he gave himself a chance to think. Creeds may be small matters, after all, but the teaching of a creed in which we do not believe is no small matter in its effects on the teacher. There are many potent reasons for fearing a heresy trial often the thought of his children’s hungry mouths and bare backs is one reason. It is a good deal easier to admire the men who went to the stake for a conviction than it is to follow them. The truth is, no minister who is honest with himself and who declares what he fully believes will have any reason to fear. The church may cast him out, but he will find a thousand voices and hearts to echo to any honest truth in his own.

“Often the preacher is so dead sure that his motive is right, that he does not stop to examine sufficiently his method. He wants to save souls, and if he can do it, as it seems to him, by crooked means more quickly than by straight ones, then he takes the crooked way. He wants to build a church, if he can build it quicker by misrepresentation, by double dealing, by beating any one, he thinks only of the church, and that overweighs any other consideration.

“Take the matter of ministers (and others, too) lying in the stories and illustrations they tell. We have all heard preachers tell as happening to them some incident which we read when we were boys; perhaps before they were born. The man is so carried away with desire to impress the truth on you that he consents to lie to make the illustration more personal and forceful. That makes it none the less a lie; but after he has told it that way a few times, he forgets that it is a lie.

“One of the principal reasons for the disrespect in which the preacher is often regarded by the business world lies in the shamefully unbusinesslike manner in which the preacher has been treated in regard to compensation for his work. If his work is worthless, why not say so and tell him to get out, and do something worth while? If it is worth doing, then he ought to be paid sufficient for a living without being compelled to become a cadger and a pauper.

“The old donation party may have had a good beginning, but it has had a bad effect on the minister’s character. Add to the moral results of being compelled to digest frozen potatoes, wooden turnips and other donation specimens, the experience of being forced into the attitude, at least annually, of a beggar, and one will begin to appreciate the difficulty the preacher has in maintaining his self-respect. When one makes it hard for a man to respect himself, how long is one likely to respect him?

“When the man in the pulpit is dependent for his daily bread on the tolerance and good will of the man in the pew; when he feels that he may get butter on his bread or even a little cake now and then if he can only get in the good graces of that smug old sinner sitting down there, it is easy to see how he has been tempted to fawn on him, how he has been tempted to speak of the old humbug’s robbery of the widow and the orphan as one of the achievements of modern commerce and civilization. It has always been ‘hard hitting the devil over the back if you are feeding his belly.’

“The preacher in the country and in the old days could get along very well between the neighborly gifts he received and the produce of his little farm or garden when these were added to his small salary. But when, without increase of salary, that same man is placed in the city in our days of swollen prices for necessities, he is hard put to it to keep out of debt and remain honest in the ministry. Under the pressure some men have turned to crooked schemes, to selling mining stocks and other bogus investments, and some have gone out of the ministry. But the greater number have stayed in and are working hard to make ends meet and to stay straight.

“Ministers have gone wrong because they have not been trained right in their professional schools; they have been educated in their local church bible schoools only for oratorical labor, and that with the intent of persuading men to certain things by dint of their eloquence. What seminaries are giving courses corresponding to those in other professional schools on professional ethics? They have gone wrong in instances because their employers (the church authority), the members, have not treated them right, have not given them a fair chance to live right; they have paid them, and are paying them less than we pay mechanics and clerks, and yet they expect the minister to live according to their social standards and that they should prove their mininsterial callings whilst authority live fat of all the collective monies aggreggated across the daughter churches or parishes.

“When the people who employ the ministers will give them an honest return for their work, when they will also encourage them to be honest in their preaching and teaching, there will be fewer unworthy ministers. When the theological schools get out of their shells and into the cities, and the preachers get out of their cloth and among folk, when they take off their garments of sanctimoniousness and get busy helping and leading others to better living, and to making this world a better place to live in, the ministers will be a good many notches higher in the world’s esteem. It is needless to say there are a great many ministers who have made good in these ways.”

We have thus a view of the clerical profession from the inside, the writer having turned state’s evidence. In the closing paragraph there is an intimation that liberal preaching, or “honest” preaching, with a discarding of the cloak of sanctimoniousness, will react on clerical morality and thus raise the preachers in the world’s esteem. That view is borne out by the figures showing that the ministers of the liberal sects are the best behaved.

Probitas Report is working on the various lack of integrity in business cases across the law courts and law enforcement agencies of cases reported for one financial crime or the other to focus on business practices and our conduct in Corporate Nigeria with the roles of these Pentecostal miniistries at their international headquarters with regards to their dogmas.

Contact: report@probitasreport.com

Stay informed and ahead of the curve! Follow The Probitas Report on WhatsApp for real-time updates, breaking news, and exclusive content—especially on integrity in business and financial fraud reporting. Don’t miss any headlines—connect with us on social media @probitasreport and visit www.probitasreport.com WhatsApp Only: +234 902 148 8737

What's Your Reaction?