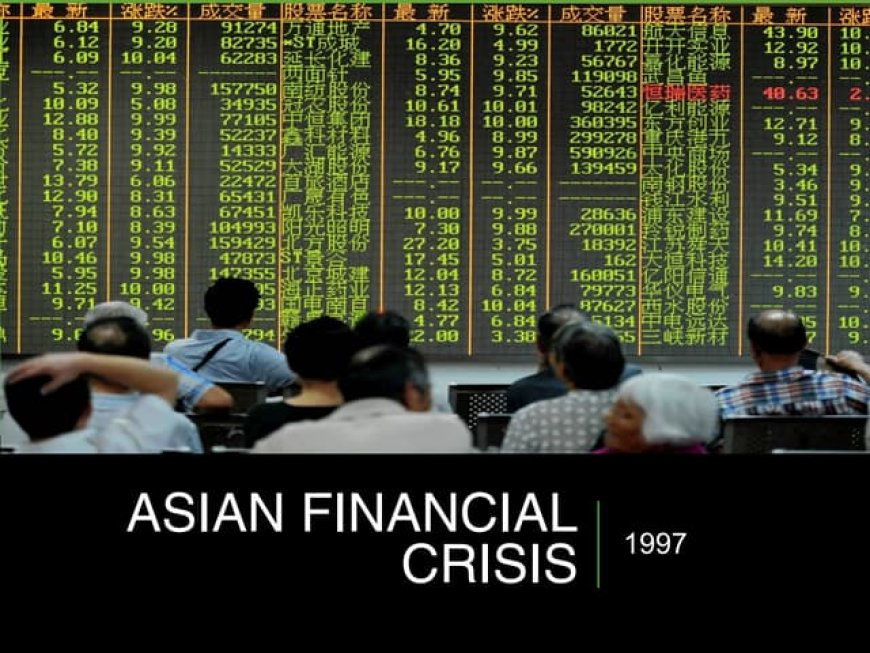

1997 Asian Financial Crisis: Critical Lessons for Today’s Economies

An in-depth analysis of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the critical lessons it offers today’s economies, especially emerging markets facing debt, inflation, and volatile capital flows.

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis changed global finance. It proved strong economic growth and moderate inflation are not sufficient protection. This event demonstrated how fixed exchange rates, foreign currency debt, and institutional failures combine to create systemic collapse. Today, emerging markets navigate a world of elevated post-pandemic debt, global inflationary pressures, and tighter financial conditions. The historical lessons from Asia require careful adaptation, not simple replication.

Understanding the 1997 Collapse

The crisis began with the collapse of the Thai baht in July 1997. Thailand maintained a quasi-fixed exchange rate pegged to the US dollar. This policy encouraged large capital inflows. Domestic banks and non-bank financial institutions borrowed heavily in foreign currency. These were short-term loans. They financed long-term property investments and equity market speculation. The fixed exchange rate created a perception of limited currency risk. Borrowers did not hedge their foreign exposures.

Rapid credit growth fueled an asset price boom. The real estate and equity markets overheated. External deficits grew. Short-term foreign debt increased relative to foreign exchange reserves. Speculative pressure mounted against the baht. The central bank intervened heavily. Reserves were depleted. Monetary policy tightened. Finally, the authorities floated the currency. The baht depreciated sharply.

Devaluation worsened the balance sheets of unhedged borrowers. Widespread corporate distress followed. Credit contracted. Asset prices collapsed. A deep recession began. The crisis moved from a currency event to a full systemic banking and corporate crisis.

South Korea experienced a different pathway. The country had a competitive export sector and no large current account deficit. Its vulnerability was high corporate leverage. Large industrial conglomerates, called chaebols, financed operations with short-term foreign borrowing. Domestic banks acted as conduits. The financial system featured close links between banks, government, and industrial groups. This led to poor risk management and soft budget constraints.

The Korean won was managed within a narrow band. This fostered a perception of stability. As regional stress intensified, international creditors reassessed risk. Rolling over short-term external debt became difficult. Liquidity pressures crippled Korean banks and corporations. Won depreciation increased the domestic currency value of foreign liabilities. Corporate solvency dissolved. A balance of payments crisis ensued.

Both cases shared a critical vulnerability. They combined capital account liberalization with de facto fixed exchange rates. This mix encouraged unhedged foreign currency borrowing. Weak prudential regulation and opaque governance allowed risks to accumulate unseen. A shift in investor sentiment triggered the rapid unraveling.

Contagion spread the crisis across borders. It moved through trade linkages. Devaluation in one country eroded the competitiveness of its neighbors. Financial channels amplified the problem. Common international banks reduced exposure across the entire region. Informational contagion and herding behavior caused investors to withdraw funds from multiple markets simultaneously. The crisis highlighted how interconnectedness accelerates regional failure.

Your Economic Landscape Has Changed

The global environment for emerging markets is different now. The post-COVID-19 period presents distinct challenges. Public and private debt levels are sharply higher. Governments expanded fiscal support during the pandemic. Central banks eased monetary policy. Many countries entered the 2020s with constrained revenue bases and concerns about debt sustainability. High interest payments and concentrated refinancing needs add pressure.

Global inflation complicates macroeconomic management. Supply disruptions and commodity price shocks contribute. Emerging market central banks face a difficult balance. They must tighten monetary policy to contain inflation. They also aim to preserve exchange-rate stability and avoid damaging financial stability. High variable-rate debt or foreign currency liabilities increase debt-servicing costs. This amplifies solvency risks.

Capital flow volatility has returned. Tightening monetary policy in advanced economies places pressure on emerging markets. Portfolio flows are volatile. The risk of sudden stops in capital remains a central concern. This is especially true for countries with large external financing needs. Significant foreign participation in local bond markets increases exposure.

The composition of capital flows has shifted. Portfolio and investment-fund flows now play a greater role. These flows respond rapidly to global financial conditions. They create market pressures even in countries with adequate reserves and prudent policies. Countries with high external debt, large current account deficits, or perceived policy uncertainty are more vulnerable. When global rates rise, risk is repriced. Currency depreciation then tightens domestic financial conditions through balance-sheet channels.

Institutional resilience has improved since 1997. Many emerging markets have more robust banking regulation and supervision. Higher capital and liquidity standards are common. Risk management and stress testing are better. More flexible exchange-rate regimes and inflation-targeting frameworks are widely adopted. Regional financial arrangements like swap lines and reserve-pooling complement multilateral support.

New sources of fragility have emerged. The expansion of non-bank financial intermediation is significant. The growth of domestic bond markets with foreign participation creates new channels for shock transmission. Reliance on market-based financing introduces complexity. Political and governance risks remain salient. They affect policy credibility. Climate-related shocks and the low-carbon transition add structural macro-financial risk. Progress is partial. Stronger frameworks increase the capacity to absorb shocks. But elevated debt, volatile capital flows, and evolving structural risks mean the potential for disruptive crises remains.

Implementing the Lessons: A Policy Framework

The legacy of the crisis is a set of guiding principles. You must adapt these principles to the complex environment of the 2020s. Proactive balance-sheet risk management is the foremost priority.

First, enhance macro-prudential regulation and financial oversight. This policy is central to containing systemic risk. It addresses pro-cyclical leverage and foreign-currency exposure. Effective tools include countercyclical capital buffers. Sectoral capital requirements for high-risk lending are important. Limits on loan-to-value and debt-service ratios help. Impose strict caps on foreign-currency borrowing by unhedged borrowers.

Effective policy requires timely information. You need granular data on bank and non-bank balance sheets. Understand off-balance-sheet exposures and interconnectedness. Conduct regular stress tests. Test for exchange-rate shocks, interest-rate spikes, and sudden capital stops. These tests help anticipate shock propagation. Strengthen supervisory independence and analytical capacity. Build legal frameworks for early intervention. Macro-prudential policy must coordinate with monetary, fiscal, and exchange-rate policy. Acknowledge the trade-offs between price stability, growth, and financial resilience.

Second, strengthen regional financial safety nets and reserve management. The Asian crisis exposed the limits of individual country reserves. Ad hoc international support is not reliable. Deepen regional safety nets. Develop reserve-pooling arrangements and bilateral swap lines. These tools reduce rollover risk. They anchor investor expectations. They provide policy adjustment space.

Regional arrangements are not a substitute for sound national policy. Manage external liability structures carefully. Implement policies to lengthen debt maturities. Encourage local-currency borrowing. Diversify the investor base. These actions reduce balance-sheet vulnerabilities. Assessments of reserve adequacy must now consider volatile portfolio flows and correlated regional shocks. Coordination between regional and global safety nets is critical. Future arrangements need clearer rules. They require greater country ownership. They must better align liquidity support with necessary structural reform.

Third, enforce governance and transparency as macro-critical goals. The crisis revealed how opaque structures hide risk. Politically connected lending and weak disclosure allowed dangers to accumulate. In the public sector, implement transparent fiscal frameworks. Adopt credible medium-term debt strategies. Ensure clear central bank communication. These actions anchor expectations. They reduce abrupt shifts in investor sentiment.

In the private sector, demand stronger corporate governance. Independent boards and rigorous audits are essential. Effective enforcement of rules mitigates moral hazard. Mandate enhanced disclosure of foreign-currency exposures. Require reporting of related-party transactions and off-balance-sheet commitments. Extend transparency requirements to non-bank financial intermediaries. Include mutual funds, pension funds, and market-based lenders. Their links with the banking system allow shocks to propagate rapidly.

For Nigeria and other African economies, these lessons are immediately relevant. The ongoing shift toward exchange rate flexibility is a necessary corrective. Continued strengthening of the banking sector is imperative. Diversifying the economic base away from single commodities reduces a major external vulnerability. You must monitor corporate foreign debt exposure. Examine the banking sector's asset quality. Assess the structure of external financing. Building institutional capacity to manage volatility is a continuous task. The goal is to achieve long-term development without sacrificing financial stability.

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis was a definitive event. It transformed the understanding of financial fragility. The core insight endures. Financial liberalization requires robust institutional foundations. Open capital accounts, fixed exchange rates, and weak regulation are a dangerous combination. The principles of proactive risk management, layered safety nets, and uncompromising transparency are not optional. They are the foundation of economic resilience. Your application of these lessons determines future stability.

References

-

Aghion, P., Bacchetta, P., & Banerjee, A. (2001). Currency crises and monetary policy in an economy with credit constraints. European Economic Review, 45(7), 1121–1150. [54]

-

Caballero, R. J., & Krishnamurthy, A. (2001). International and domestic collateral constraints in a model of emerging market crises. Journal of Monetary Economics, 48(3), 513-548.

-

Calvo, G. A. (1998). Capital flows and capital-market crises. The simple economics of sudden stops. Journal of Applied Economics, 1(1), 35–54.

-

Carney, R. (Ed.). (2009). Lessons from the Asian financial crisis. Routledge.

-

Corsetti, G., Pesenti, P., & Roubini, N. (1999). What caused the Asian currency and financial crisis? Japan and the World Economy, 11(3), 305–373.

-

Eichengreen, B. (1999). Toward a new international financial architecture. A practical post-Asia agenda. Institute for International Economics.

-

Furman, J., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1998). Economic crises. Evidence and insights from East Asia. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1998(2), 1–135.

-

Kaminsky, G. L., & Reinhart, C. M. (1999). The twin crises. The causes of banking and balance-of-payments problems. American Economic Review, 89(3), 473–500.

-

Krugman, P. (1998). What happened to Asia? Unpublished manuscript.

-

Mishkin, F. S. (1999). Lessons from the Asian crisis. Journal of International Money and Finance, 18(4), 709–723.

-

Morgan, R. (2009). Lessons from the global financial crisis. The relevance of Adam Smith on morality and free markets. Connor Court Publishing.

-

Muchhala, B. (Ed.). (2007). Ten years after. Revisiting the Asian financial crisis. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

-

Perry, G. E., & Lederman, D. (1998). Financial vulnerability, spillover effects, and contagion. Lessons from the Asian crises for Latin America. World Bank.

-

Radelet, S., & Sachs, J. (1998). The East Asian financial crisis. Diagnosis, remedies, prospects. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1998(1), 1–90.

-

Rodrik, D., & Velasco, A. (2000). Short-term capital flows. In Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics 1999 (pp. 59–90). World Bank.

-

Wyplosz, C. (2001). How risky is financial liberalization in developing countries? Comparative Economic Studies, 43(4), 1–26.

About The Author:

Dr Ohio O. Ojeagbase is a leading expert in corporate governance, financial security, credit administration, and debt recovery in Nigeria and across Africa. He is a chief proponent of Integrity In Business culture amongst Corporate SMEs, and advises banks, religious institutions, and high-net-worth clients on board effectiveness, debt recovery, and credit culture reform. Dr Ojeagbase combines decades of professional experience with rigorous research, currently pursuing yet another doctorate - DBA in Sustainable Business and Corporate Governance at Afe Babalola University Ado-Ekiti (ABUAD) Business School, Ibadan. His work bridges academic insight and practical strategy to strengthen institutional accountability and economic resilience. He specializes in debt recovery & re-engineering, governance advisory, private investigation, and financial risk management. His research focuses on sustainable business systems, regulatory reform, and improving corporate and banking sector performance. Dr Ojeagbase’s thought leadership equips policymakers, executives, and investors to implement ethical, resilient, and results-driven financial and corporate practices.

What's Your Reaction?